Up to now the focus has been on managing “hot spots” in the COVID lockdowns of Melbourne and Victoria. We have identified four key factors that might help explain why we see high rates of COVID-19 cases in some parts of the city. Our analysis also suggests a phased easing of lockdown could start with reopening “cold spots” with few or no cases of COVID-19.

And reopening the state as soon as reasonably possible is of concern from many perspectives. The federal government and business groups have led calls to ease lockdowns.

Mental health experts are also very concerned about an impending mental health crisis. Others are warning about the growth in family violence. There are also growing concerns about the gap in education of young children and their mental health risks arising from isolation.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has expressed frustration at closures of schools and state and territory borders. He has asked the national cabinet to agree on a definition of hot spots used to justify closures. This article raises a related idea with a focus on Melbourne: rather than waiting for hot spots to fade out, cold spots could possibly be reopened earlier.

Some parts are hit much harder than others

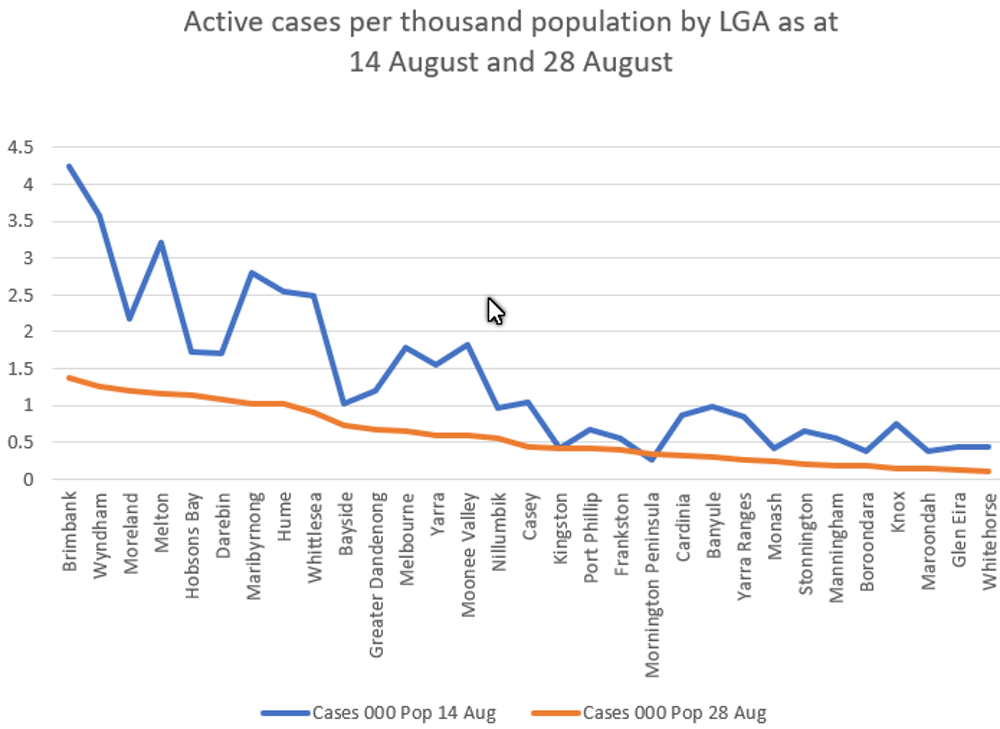

Our recent paper highlighted the wide disparities in numbers of active COVID cases per 1,000 population across Melbourne. Local government areas (LGAs) in the north and west have had much higher numbers, relative to population, than those in the south and east.

The chart below shows an encouraging picture. As active case numbers fell between August 14 and 28, the north-west/south-east disparity narrowed. Numbers fell a little faster in the north and west.

Changes in rate of active COVID-19 cases across Melbourne by local government area.

However, the 16 lowest case rates (as of August 28) remained in the south and east. The nine highest were in the north and west.

A continued fall in case numbers across Melbourne will eventually justify reopening across the city. But the current disparity between north-west and south-east suggests reopening at different times in different places is a live option. Cold spots – groups of LGAs with the lowest case rates – could open sooner.

What factors might explain the divide?

Seeking to gain insights that might explain the differences between areas, we identified 30 variables for which census, population health, unemployment or other public data are readily available. A number of these variables were significantly correlated with active case numbers.

We found positive correlations (active case numbers increased along with these factors) for:

- population

- population growth rate from 2011 to 2016

- persons per dwelling

- unemployment rate

- adult smokers

- fair or poor health.

We found negative correlations (active numbers fell) for:

- English-only is spoken at home

- population aged 80 or over

- socioeconomic status, as shown by the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ SEIFA Index.

Four variables explained 63.9% of the variance in active case numbers by LGA as at August 14. Factors such as the unemployment rate, SEIFA Index and fair/poor health dropped out, as these were significantly correlated with other retained variables.

The four retained variables were:

- resident population – a larger LGA population is associated with more active case numbers

- percentage speaking English-only at home – a lower proportion is associated with more active cases, emphasising the importance of language-appropriate COVID messaging

- percentage of the population aged 80 and over – a larger proportion is associated with fewer active cases, suggesting good risk awareness in this vulnerable age group (although the impacts in many aged care homes have been shocking)

- percentage of smokers – a higher rate is associated with larger active case numbers, perhaps suggesting respiratory vulnerability and/or lower risk awareness of this group.

As active case numbers have come down, the predicted impact of each of these four variables has also reduced. In combination, however, they still explain a similar proportion of the variance in active case numbers by LGA as in the peak period.

Interestingly, the effect of English-only spoken at home on the variance in active case numbers declined substantially between August 14 and 28. This trend suggests some success in language-appropriate messaging over that time.

Staged reopening poses issues for equity

Of the four included variables, the effect of the proportion of adult smokers has shown the smallest relative improvement as active case numbers have fallen. At LGA level, adult smoking is highly correlated with unemployment rate (+), reported fair/poor health (+), productivity (-) and the SEIFA Index (-).

These linkages suggest the burden of spatial disadvantage is having a lingering impact on active case numbers. As a result, a staged re-opening would pose equity concerns.

The growing economic costs and adverse impacts of lockdown on many already disadvantaged people underline the importance of opening up areas in Melbourne and Victoria as soon as possible. The costs are both personal and societal. A failure to halt the decline in well-being will have continuing serious consequences, adding to inequality in Australia.

Early reopening of parts of Melbourne with the lowest active case numbers, which are concentrated in the south and east, is a policy option. However, action must then be taken to avoid reinforcing entrenched disadvantage in the north and west.

Early commitments by all levels of government to implementing the wide-ranging plans in the recently released North and West Melbourne City Deal Plan 2020-2040 would help. Good starting points for reducing disadvantage include upgrading mixed-use activity centres across the city’s north and west and immediately improving medium-capacity transit services in the Suburban Rail Loop corridor.

Please note: this article has been republished from the Conversation 3/9/20